I

Solomon, Great Hall, Bart’s Hospital

Quatuor pour la fin du temps, St Paul’s Cathedral

New Dark Age, Royal Opera House, London

With the whole world of classical music engaged in streaming, live events are few and far between. But it’s on these that the future of the art will eventually have to be built, step by painful step. I have already praised the Wigmore Hall for dauntlessly forging ahead with a full programme; here is a report on three more brave events, each of which offers a possible pointer – one can’t be more definite that that – towards the shape of things to come.

First, to the Great Hall of Bart’s Hospital, a magnificent and little-known 18th-century building which you approach via some huge frescos by William Hogarth, who had taken time off from his satirical work to celebrate in paint the hospital’s healing activities.

Handel too was a supporter of such work, helping to set up the Foundling Hospital, which later became the Coram Foundation (which took in, and cared for, children the poor had left on its doorstep). So it’s appropriate that Handel’s oratorio Solomon should become the musical cornerstone for the first of a travelling series of concerts staged by Harry Bicket and the English Concert. It’s also appropriate that this should be a period-instrument ensemble: in every respect we are firmly rooted in the 18th century.

Every respect, that is, apart from the pandemic, which results in a concert unlike any I have ever attended before. With Dame Sarah Connolly leading a stellar line-up of soloists, the performance is superb.

Dame Sarah Connolly and Harry Bicket at Barts Hospital

Dame Sarah Connolly and Harry Bicket at Barts Hospital

But here’s the strange thing: I am part of an audience of just ten people; all the others – thousands of them – are at home, receiving the concert via streaming. The rest of the hall’s vast expanse is given over to the singers and musicians, each distanced from his or her neighbours by a six-foot gap. We favoured ten – and the thousands watching at home – are very reasonably invited to make donations; these stalwart musicians’ grants will only go so far, and they have mouths to feed.

Next, to an even more splendid edifice – St Paul’s Cathedral – for an extraordinary event. Here the physical audience of 300 people (plus streamed thousands) has come to hear Olivier Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps – Quartet for the End of Time. And the symbolism of that choice of repertoire feels just right for our own perilous moment in history. Messiaen composed it while in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany, and had to use the available musicians, odd though his line-up sounds: violin, cello, clarinet, and a battered old piano which he would play himself. They premiered it in the freezing cold of January 1941, for an audience of 400 fellow-prisoners and Nazi guards.

What we privileged 300 experience is awesome. Messiaen’s own commentary on the first of this visionary work’s tableaux spoke of the awakening of the birds at four in the morning: “A solo blackbird or nightingale improvises, surrounded by a shimmer of sound, by a halo of trills lost very high in the trees”. And for us Joseph Shiner’s clarinet sings ecstatically high, its sounds echoing and re-echoing through the assorted acoustic chambers of this unique space. The final tableau, with the violin reaching heavenwards while the piano gently underpins it, leaves us all in a long, stunned silence.

There were moments when the building’s exceptionally long reverberation time added too many extra layers of overtones to this already acoustically complex work, but as it progressed, the textures became ever more magical, with Ariana Kashefi’s persuasive cello underpinning the flights of Emily Sun’s violin and Alexander Soares’s piano. This work may be frequently played, but it can never have sounded as transcendental as this. All credit to the City Music Foundation for putting on this event, and to the cathedral’s administration for making this their first concert after seven months without music. They should definitely invite the players back for a repeat, or even two.

My third visit is to the Royal Opera House, for an operatic double bill entitled New Dark Age. To reach my seat I must make a labyrinthine journey along corridors and up and down stairs, so careful are they that I should not collide and share my breath with anybody coming in the opposite direction. The auditorium is about one third full, with the other seats taped off. It all feels strange, but it’s still the Covent Garden we know and love.

Peter Brathwaite as Martin Carter in The Knife of Dawn ©Tristram Kenton/ROH

Peter Brathwaite as Martin Carter in The Knife of Dawn ©Tristram Kenton/ROH

The Knife of Dawn, the first of these works, is by the British composer Hannah Kendall, whose commission to write a piece for the opening night of this year’s Proms confirmed her position as the go-to young black composer for cutting-edge but accessible music.

This work is based on the true story of the Guyanese poet and activist Martin Carter who was imprisoned for ‘sedition’ by the British government in the Fifties, and whom we meet as he goes on hunger strike in his cell. Semi-staged, with Carter’s iron bedstead as the only prop, this show makes huge demands of its protagonist, who must hold things together supported by three singers in the pit, plus a string trio with harp; newsreel footage of Guyana in the Fifties is intermittently projected onto a screen.

The artistic challenge Kendall and her librettist Tessa McWatt have set themselves would tax the most experienced composer-librettist team, since all the drama in this piece must be musical and emotional. Nothing “happens”: Carter simply rails against his oppression, gets weakened physically and mentally by hunger, and tremulously hopes that the pen will be mightier than the sword.

Kendall’s instrumental music, like her Proms score, has a Japanese economy and grace, and her word-setting follows the style set by Britten, but the libretto seldom rises above the level of dull monotony. No praise could be too high for baritone Peter Brathwaite, who takes the central role and gives a heroic performance. With perfect diction and a fine sense of timing, he manages to invest his part with pulsating believability. But the fact that composer and librettist both share Carter’s Guyanese heritage is not qualification enough to save the audience from a very heavy hour. This production could have benefited greatly from work-shopping, which might possibly have allowed its flaws to be addressed.

Susan Bickley, Nadine Benjamin and Anna Dennis in A New Dark Age ©Tristram Kenton/ROH

Susan Bickley, Nadine Benjamin and Anna Dennis in A New Dark Age ©Tristram Kenton/ROH

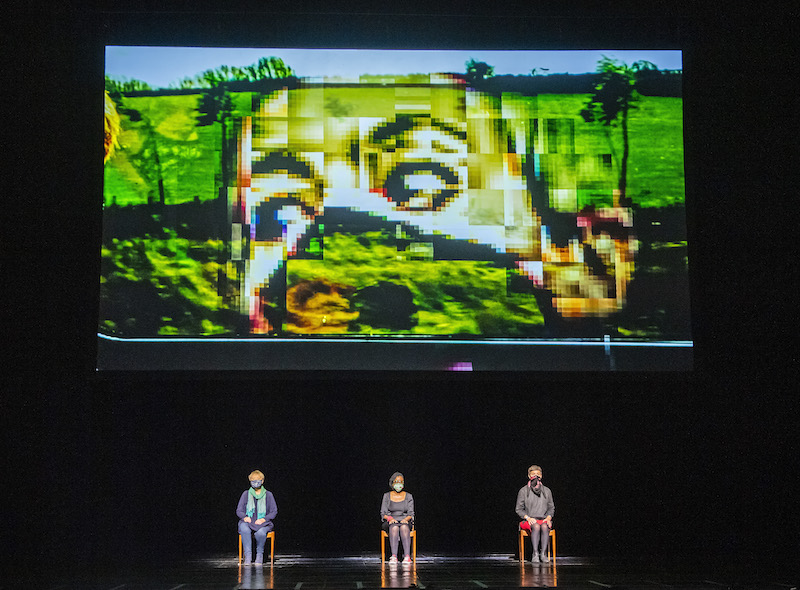

The second part of this semi-staged double-bill, A New Dark Age, consists of three works by avant-garde female composers – Anna Meredith, Missy Mazzoli, and Anna Thorvaldsdottir – which run as a seamless whole. The stage is bare apart from three chairs and a giant screen of which, from my restricted-vision seat, I can see just one small corner, so I can’t comment meaningfully on the projections.

With three soloists, a chorus, electronica, and a small instrumental ensemble, the works are musically ambitious, and get finely nuanced direction from Natalie Murray Beale. There are moments of heavy metal, and snatches of lovely Nordic devotional part-singing from Susan Bickley, Anna Dennis, and Nadine Benjamin, plus many other styles in between, but the works, though disparate, seem to merge into an uneasy single entity. Again, work-shopping might have induced some timely second thoughts.

Yet one must commend Covent Garden for committing its main stage, in these difficult times, to an out-and-out experimental programme, and it’s heartening that demand for tickets should have been so high that the auditorium could have been filled twice over. Next month the Royal Opera will address a broader church, with a series of concert performances of Handel’s Ariodante and Verdi’s Falstaff, both jewels in the ROH repertory, and both starring glittering names including Gerald Finley and Sophie Bevan, Simon Keenlyside and Bryn Terfel. Little by little, opera in London is returning to life.