Salome, English National Opera

‘We begin in darkness,’ proclaims an essay by Elena Manafi in the programme, ‘a confrontation with the abyss of the feminine.’ Adena Jacobs’s new production of Salome is described by ENO as a ‘boldly feminine interpretation’ by ‘an all-female creative team’, and, given that the curtain rose at the precise moment when an altercation in a lift was changing the face of sexual politics in America, their timing could not have been better.

And it does indeed start with a blackout. When the lights go up, it’s on what looks like a queue of punters roped off on the pavement outside a nightclub, with an illuminated glass tank of water above their heads in which a female figure languidly floats. For nightclub read Herod’s banqueting hall: Narraboth (Stuart Jackson) extols the beauty of the Tetrarch’s step-daughter Salome (Allison Cook), who stands grimly aloof as she is told of Herod’s sexual designs on her, and as her mother’s page (Clare Presland) predicts that terrible things will happen tonight.

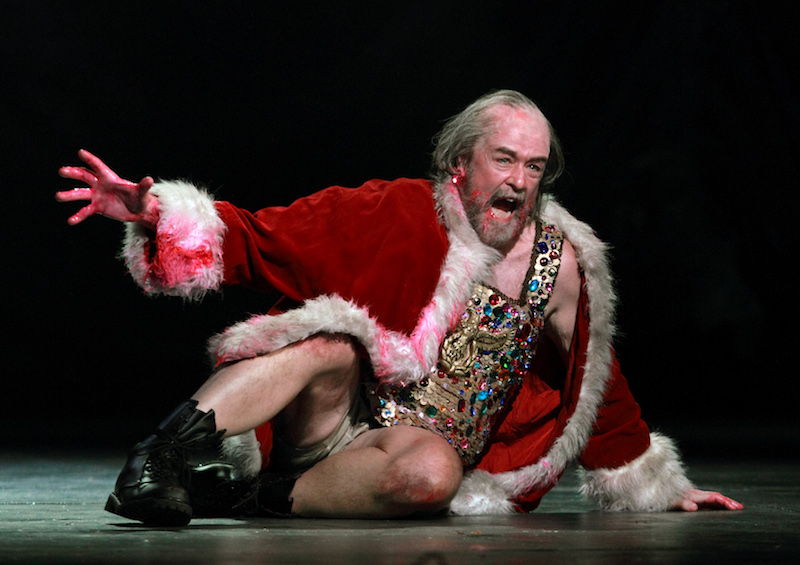

Michael Colvin as Herod ©Catherine Ashmore

Michael Colvin as Herod ©Catherine Ashmore

We first hear the voice of David Soar’s Jokanaan (alias John the Baptist) over a loudspeaker, but the initial encounter between him and Salome (with Narraboth watching in horror) works well musically: Cook’s light and girlish soprano contrasts nicely with Soar’s sonorous bass, and her alternating lust and disgust is radiantly amplified instrumentally by the orchestra under Martyn Brabbins’s direction.

But there are problems. The prophet’s mouth making its stentorian pronouncements is projected, greatly magnified, onto the wall behind him: this chimes with Salome’s lascivious obsession with kissing him, but the camera involved is attached to his face like a beak, and when he turns his back on us he looks – all wired up – like a dog on a lead. Meanwhile Narraboth is making a video of the proceedings: no wonder he’s driven to messily kill himself. All this seems more about gadgetry than love.

But it’s also about the scarlet high-heeled slippers which the otherwise ragged prophet wears, then kicks off, and which Salome then climbs into. Stripped to the waist and with her back to the audience, she masturbates in her trance-like identification with the love-object. After this intimation of Manafi’s dark feminine abyss, the show sweeps on.

Allison Cook as Salome ©Catherine Ashmore

Allison Cook as Salome ©Catherine Ashmore

Now we enter the theatre of the absurd. A life-size headless carcass of a horse is dragged on and disembowelled, its innards proving to be garlands of flowers. Four female dancers in boxer shorts come on, and wait in a corner. A girl gets dunked in the nightclub tank. Presiding over events is Michael Colvin’s Herod clad in an ermine-edged Father Christmas coat and not much else, but his incarnation of paranoid derangement is highly convincing, as is Susan Bickley’s baleful Herodias.

And the dance of the seven veils? Like the original Salome in 1905 – who at this indecent point insisted that a dancer should take her place – Cook simply doesn’t do it (well, how could a proudly ‘feminine’ production permit such a sexist provocation?) While Cook stands mutinously still under a spotlight, the aforementioned quartet impersonate a robotic keep-fit class. ‘Wonderful!’ gushes Herod when they’ve finished, in another of this show’s little mysteries. The negotiating argy-bargy between him and his step-daughter, who exhibits an EU-style inflexibility in her demand for Jokanaan’s head, is beautifully sung.

Cook’s delivery of the triumphant encomium to the severed head is likewise beautiful, though as she keeps it in a plastic bag and doesn’t even look at it, the dramatic effect is somewhat weakened. And she’s not finally crushed under a pile of shields as the libretto has it: with Herodias providing the wherewithal to drink, she sees herself off in front of a backdrop of pink roses, in the middle of which is a circular black orifice. The abyss!!!

Le tout Londres was present on first night, including more political pundits than I’ve ever seen in an opera audience – doubtless driven by the repetitive boredom of real politics to take refuge in sexual ones. The show may be a hoot, but the music is tremendous.

★★★